The Mental Health of the “Model Minority”

My father sometimes tells me stories relating to his upbringing in the small village of Salumber, India. We were never a rich family, and he often reminisces on walking multiple kilometers every morning just to attend school and sometimes having to live without running water or electricity. My grandfather was a public school teacher, which meant we did not have much, most of the time. However, my father always wanted a better life for himself. He considered education the best way for him to achieve one, so he devoted himself to his studies. He would regularly read and reread his textbooks into the early hours of the morning, having nothing but a candle to use for light because the power was never on. When his friends would invite him to take it easy, just for a day, and play cricket outside with them, my father would refuse. He knew that if he ever faltered, even for a moment, he might fall off the path he had so carefully charted for himself. And eventually, his years of resolve paid off: he had made it. He graduated from a highly ranked engineering school in India, and despite only having a limited knowledge of English, immigrated to America and achieved the Dream.

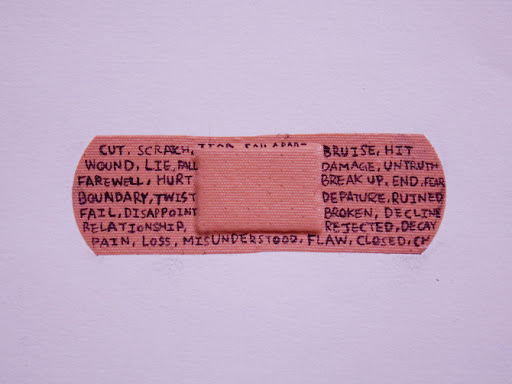

Before I finally confessed to my parents that I was suffering from depression, my father’s stories would constantly reverberate throughout my mind. They were always linked to a particular amorphous quality, relating to a word in Hindi called “sharam”, which roughly translates to “shame”. How shameful was it for me to possibly feel depressed, when my parents had gone through so much, given up so much, just for me to be here in America, where I was provided with everything I could possibly want? And so, because of my sharam, I continued to suffer, and suffer alone. On the surface level, I was doing fine, maintaining a high GPA at a difficult school and seeming to be a relatively “normal” person, whatever that entails. However, the pressure to maintain my academic success and continue to be the model son and the “model minority” caused me to constantly doubt myself, even hate myself, with every tiny mistake I made. And yet, I continued to remain silent. It was not until one particularly awful night, when I was seriously considering harming myself, that I finally broke down in front of my parents and let my tears speak for me.

My experiences are not wholly unique- according to Mental Health America, 13% of the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community was diagnosed with a mental illness in the past year. Many of them report feeling similar feelings of pressure to live up to the impossible ideal of being the “model minority”, compounded with “immigrant guilt” and cultural stigma prohibiting them from talking about mental health. Moreover, much of the AAPI community also faces language barriers, inaccessibility to mental health resources, and sometimes, racism, preventing them from seeking or receiving the care they need. While I was fortunate enough to have parents who took me to therapy, most don’t receive this privilege, with South Asian Americans having the lowest rate of utilization of mental health services of any ethnicity.

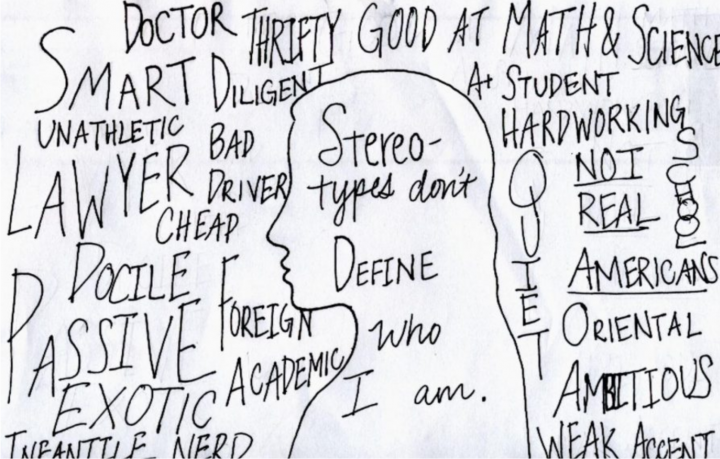

There are no easy ways to challenge stigma, especially when it is so deeply intertwined with broader cultural, racial, and psychological phenomena, as it is in the AAPI community. However, simply talking about it can help tremendously. Living in silence simply allows pain to fester and grow, and further isolates those suffering. Starting honest, real, and open conversations about mental health in the AAPI community is a necessary first step, and one that should include all voices. This alone is not enough: even when AAPI individuals do go to therapy, their therapists may not know how to address the particular cultural and racial nuances of their experiences. Thus, it is also important to promote cultural competency training for mental health professionals and encourage more AAPI individuals to enter the mental health field, considering that it is currently 86% white. Moreover, challenging prevailing assumptions and narratives about what it means to be Asian American is absolutely necessary. Deconstructing the idea of a “model minority” is particularly important, considering the limitations and pressure it puts on AAPI individuals, and how it erases the experiences of disadvantaged AAPI communities and anyone else who doesn’t fit its restrictive image.

Individuals wishing to challenge mental health stigma in the AAPI community can support organizations like WE ARE SAATH and AAPCHO, who focus on the issue. Additionally, they can reach out to local policymakers and encourage them to create policies to address the disparities in mental health care. While these issues may seem difficult to confront, starting now, even in small ways, can help create lasting and meaningful change.